Darts in Paciano, Italy

Just as it was whales that brought award-winning environmental writer (and former Greenpeace staffer) Kieran Mulvaney to Paciano, Italy, a few weeks ago it was somewhat the same for me...

I made the trip to Umbria - the "Green Heart of Italy" - to join a friend (and former employer), Brian Davies, and his wife, Gloria (originally with the Cousteau Society), to spend time with another friend, Dr. Sidney Holt. In Mulvaney's words (Washington Post, 2014) Holt is the "grey eminence of what might be called the 'Save the Whales' movement." Davies is the grey eminence of the "Save the Seals" movement.

Believe what you want about PETA, WWF, the Humane Society of the United States and other similar charities - they all do fine work. But it is Holt and Davies who were the pioneers and still are champions of compassion for sentient beings. Since the 1960s, Holt and Davies have blazed the trail others follow today.

Holt is one of the fathers of modern fisheries science and is, perhaps, best known for the book he authored with Ray Beverton in 1957, On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations, which is still used in classrooms today. For 25 years, he served with various United Nations' agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). After he retired in 1979, he was a pacesetter within the International Whaling Commission, particularly within the Scientific Committee, and is credited by many as the architect of the sound scientific arguments that led to massive commercial catch reductions and ultimately the end to the killing of most baleen whale species by the end of the 1960s.

Holt is one of the fathers of modern fisheries science and is, perhaps, best known for the book he authored with Ray Beverton in 1957, On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations, which is still used in classrooms today. For 25 years, he served with various United Nations' agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). After he retired in 1979, he was a pacesetter within the International Whaling Commission, particularly within the Scientific Committee, and is credited by many as the architect of the sound scientific arguments that led to massive commercial catch reductions and ultimately the end to the killing of most baleen whale species by the end of the 1960s.

Davies founded the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) in 1969 and grew the organization to one of the largest (more than two million members), wealthiest (upwards of $85 million annually), and most effective in the world. Davies is probably most heralded for crafting IFAW's victory in 1983 when the European Union banned the importation of newborn white coated harp seals and hooded seal pups, causing the cruel Canadian commercial seal hunt to crash. When he retired from IFAW in the late 1990s, Davies founded Network for Animals, which today works to stamp out the dog meat trade in the Philippines as well as badger culling and hunting with hounds in the UK and rhinoceros and elephant culling in South Africa.

Yes, pioneers. They taught me so much. Spending time with them was like being caught in some weird cetacean-pinniped vortex. The only thing that belies the genius of their extraordinary careers is that for some unknown reason they both follow my darts ramblings.

At dinner the first night, I remarked to Holt (the person singularly most responsible for turning my hair grey), "I know we argued a bit over the years but I want you to know how grateful I am for all you taught me, there's just so much." The twinkle I remembered so well appeared in Sidney's eyes, and he replied, "Thank you, but I can't think of anything I learned from you."

At dinner the first night, I remarked to Holt (the person singularly most responsible for turning my hair grey), "I know we argued a bit over the years but I want you to know how grateful I am for all you taught me, there's just so much." The twinkle I remembered so well appeared in Sidney's eyes, and he replied, "Thank you, but I can't think of anything I learned from you."

Syndey's a funny man. He's just about 90 now, and his eyesight isn't as good as it once was. So probably he didn't notice the little worm I slipped into his pasta. Probably he did notice, just a moment ago, that I spelled his name wrong.

Seriously, over the years Holt did teach me a great deal. I learned that whales are "really big fish" and a null hypothesis is a "type of ape." One day at lunch in Paciano, he shared a long story about Leonardo da Vinci, who I now know invented the cotton gin.

I learned a lot from Davies too. For example, he taught me how to swear.

The trip turned out to be much more than an opportunity to renew cherished acquaintances. Thanks to Holt and another old friend, Lesley Busby, I learned about olives, wine and pasta. Well, actually, I didn't learn a thing. But I did drink a hell of a lot of wine and eat pasta twice a day, every day. I also picked an olive, just one, from a real olive tree among Holt's personal grove of hundreds.

Best of all, thanks to Busby and considering my limited interest in (Holt would say "aptitude" for) anything intellectual, I also had the opportunity to throw darts at one of the most unique locations I have ever encountered.

Best of all, thanks to Busby and considering my limited interest in (Holt would say "aptitude" for) anything intellectual, I also had the opportunity to throw darts at one of the most unique locations I have ever encountered.

Settled since Etruscan and ancient Roman times, Paciano is about a two-hour drive north of Rome, located in the Province of Perugia on the border of Tuscany. Set high atop rolling hills, surrounded by silvery olive groves as far as the eye can see and with Lake Trasimeno (where Hannibal defeated the Romans in 217 B.C.) in the distance, it's proudly known as one of "The Most Beautiful Villages in Italy." The spectacular old town is a walled fortress built in the 1300s. My three-day home away from home was Relais Mastro Cinghiale, the converted village mill just inside the walls.

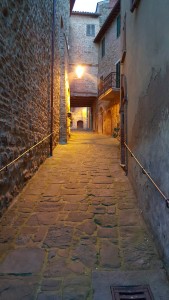

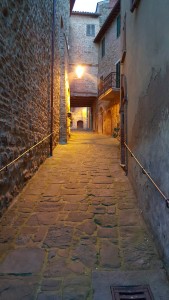

On the night before my final evening in Paciano, I maneuvered along the brick and cobblestone alleyways that weave their way below towering stone walls to the small town square, the Piazza della Repubblica. Countless unseen pigeons cooed from the rooftops as I made my way.

Just off the side of the square, across the way from the local pub, Il Baretto, I was met by my host for the darts, Daniele Talozzi. There, truly out of place in the far corner of this medieval setting, stood a Cyberdine electronic darts machine. I'd never before seen such a machine. Similar to an old Harrows Quadro steel-tip board, this electronic machine not only had an extra ring but the size of everything was the same as a conventional board.

Talozzi, an animal lover, and his team compete in the FIDART Federation (Federazione Italiana Dart) and throw out of the Joker Casino in Bettole, just across the border into Tuscany in the Province of Siena. My plan was to get to Bettole the following night to watch his team compete but, regrettably, an early departure for Rome-Fiumicino Airport the next morning caused me to reconsider.

So Talozzi and I threw darts. I whooped his ass silly!

So Talozzi and I threw darts. I whooped his ass silly!

Sometimes I lie.

Talozzi threw darts. He's a quality player (he'd have been even better if it hadn't been cold and he wasn't wearing a long-sleeve shirt). I threw rocks.

While I may have picked off a few legs - I vaguely remember taking out 74 (t14, d16) at one point - I honestly don't remember any other positive moment. I was missing by inches. So I needed a whole new set of excuses for the occasion.

"I picked an olive today - my arm is sore."

"A pigeon pooped on me."

"At home we throw four darts."

I think these were all very reasonable excuses, but Talozzi didn't speak much English, so they had no effect.

Talozzi was also saying things to me. Even though I speak no Italian, I understood. Such is the universal "language of darts." Several times he corrected my score. Several times he reminded me to press the button after my turn.

At least a half dozen times he shrugged his shoulders and (I think) apologized when the machine subtracted 60 points from his score as he picked a dart off the brick floor. Seriously, why does a bounce out get you 60 points when a t1 that sticks gets you only three? Something is massively screwed up in the Italian space-time continuum.

We called it a night around 11:00 p.m. At least I think we did...

We called it a night around 11:00 p.m. At least I think we did...

Talozzi said, Arrivederci, which I believe means "goodbye" or "until we meet again," or some such thing. If not, he may still be standing at the line at the Piazza della Repubblica. Maybe I was supposed to find him a beer.

I weaved my way back to the Relais Mastro Cinghiale. I was attacked by a horde of Etruscans en route, but still, I had a "whale" of a time.

From the Field,

Dartoid

I made the trip to Umbria - the "Green Heart of Italy" - to join a friend (and former employer), Brian Davies, and his wife, Gloria (originally with the Cousteau Society), to spend time with another friend, Dr. Sidney Holt. In Mulvaney's words (Washington Post, 2014) Holt is the "grey eminence of what might be called the 'Save the Whales' movement." Davies is the grey eminence of the "Save the Seals" movement.

Believe what you want about PETA, WWF, the Humane Society of the United States and other similar charities - they all do fine work. But it is Holt and Davies who were the pioneers and still are champions of compassion for sentient beings. Since the 1960s, Holt and Davies have blazed the trail others follow today.

Holt is one of the fathers of modern fisheries science and is, perhaps, best known for the book he authored with Ray Beverton in 1957, On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations, which is still used in classrooms today. For 25 years, he served with various United Nations' agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). After he retired in 1979, he was a pacesetter within the International Whaling Commission, particularly within the Scientific Committee, and is credited by many as the architect of the sound scientific arguments that led to massive commercial catch reductions and ultimately the end to the killing of most baleen whale species by the end of the 1960s.

Holt is one of the fathers of modern fisheries science and is, perhaps, best known for the book he authored with Ray Beverton in 1957, On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations, which is still used in classrooms today. For 25 years, he served with various United Nations' agencies including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). After he retired in 1979, he was a pacesetter within the International Whaling Commission, particularly within the Scientific Committee, and is credited by many as the architect of the sound scientific arguments that led to massive commercial catch reductions and ultimately the end to the killing of most baleen whale species by the end of the 1960s.

Davies founded the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) in 1969 and grew the organization to one of the largest (more than two million members), wealthiest (upwards of $85 million annually), and most effective in the world. Davies is probably most heralded for crafting IFAW's victory in 1983 when the European Union banned the importation of newborn white coated harp seals and hooded seal pups, causing the cruel Canadian commercial seal hunt to crash. When he retired from IFAW in the late 1990s, Davies founded Network for Animals, which today works to stamp out the dog meat trade in the Philippines as well as badger culling and hunting with hounds in the UK and rhinoceros and elephant culling in South Africa.

Yes, pioneers. They taught me so much. Spending time with them was like being caught in some weird cetacean-pinniped vortex. The only thing that belies the genius of their extraordinary careers is that for some unknown reason they both follow my darts ramblings.

At dinner the first night, I remarked to Holt (the person singularly most responsible for turning my hair grey), "I know we argued a bit over the years but I want you to know how grateful I am for all you taught me, there's just so much." The twinkle I remembered so well appeared in Sidney's eyes, and he replied, "Thank you, but I can't think of anything I learned from you."

At dinner the first night, I remarked to Holt (the person singularly most responsible for turning my hair grey), "I know we argued a bit over the years but I want you to know how grateful I am for all you taught me, there's just so much." The twinkle I remembered so well appeared in Sidney's eyes, and he replied, "Thank you, but I can't think of anything I learned from you."

Syndey's a funny man. He's just about 90 now, and his eyesight isn't as good as it once was. So probably he didn't notice the little worm I slipped into his pasta. Probably he did notice, just a moment ago, that I spelled his name wrong.

Seriously, over the years Holt did teach me a great deal. I learned that whales are "really big fish" and a null hypothesis is a "type of ape." One day at lunch in Paciano, he shared a long story about Leonardo da Vinci, who I now know invented the cotton gin.

I learned a lot from Davies too. For example, he taught me how to swear.

The trip turned out to be much more than an opportunity to renew cherished acquaintances. Thanks to Holt and another old friend, Lesley Busby, I learned about olives, wine and pasta. Well, actually, I didn't learn a thing. But I did drink a hell of a lot of wine and eat pasta twice a day, every day. I also picked an olive, just one, from a real olive tree among Holt's personal grove of hundreds.

Best of all, thanks to Busby and considering my limited interest in (Holt would say "aptitude" for) anything intellectual, I also had the opportunity to throw darts at one of the most unique locations I have ever encountered.

Best of all, thanks to Busby and considering my limited interest in (Holt would say "aptitude" for) anything intellectual, I also had the opportunity to throw darts at one of the most unique locations I have ever encountered.

Settled since Etruscan and ancient Roman times, Paciano is about a two-hour drive north of Rome, located in the Province of Perugia on the border of Tuscany. Set high atop rolling hills, surrounded by silvery olive groves as far as the eye can see and with Lake Trasimeno (where Hannibal defeated the Romans in 217 B.C.) in the distance, it's proudly known as one of "The Most Beautiful Villages in Italy." The spectacular old town is a walled fortress built in the 1300s. My three-day home away from home was Relais Mastro Cinghiale, the converted village mill just inside the walls.

On the night before my final evening in Paciano, I maneuvered along the brick and cobblestone alleyways that weave their way below towering stone walls to the small town square, the Piazza della Repubblica. Countless unseen pigeons cooed from the rooftops as I made my way.

Just off the side of the square, across the way from the local pub, Il Baretto, I was met by my host for the darts, Daniele Talozzi. There, truly out of place in the far corner of this medieval setting, stood a Cyberdine electronic darts machine. I'd never before seen such a machine. Similar to an old Harrows Quadro steel-tip board, this electronic machine not only had an extra ring but the size of everything was the same as a conventional board.

Talozzi, an animal lover, and his team compete in the FIDART Federation (Federazione Italiana Dart) and throw out of the Joker Casino in Bettole, just across the border into Tuscany in the Province of Siena. My plan was to get to Bettole the following night to watch his team compete but, regrettably, an early departure for Rome-Fiumicino Airport the next morning caused me to reconsider.

So Talozzi and I threw darts. I whooped his ass silly!

So Talozzi and I threw darts. I whooped his ass silly!

Sometimes I lie.

Talozzi threw darts. He's a quality player (he'd have been even better if it hadn't been cold and he wasn't wearing a long-sleeve shirt). I threw rocks.

While I may have picked off a few legs - I vaguely remember taking out 74 (t14, d16) at one point - I honestly don't remember any other positive moment. I was missing by inches. So I needed a whole new set of excuses for the occasion.

"I picked an olive today - my arm is sore."

"A pigeon pooped on me."

"At home we throw four darts."

I think these were all very reasonable excuses, but Talozzi didn't speak much English, so they had no effect.

Talozzi was also saying things to me. Even though I speak no Italian, I understood. Such is the universal "language of darts." Several times he corrected my score. Several times he reminded me to press the button after my turn.

At least a half dozen times he shrugged his shoulders and (I think) apologized when the machine subtracted 60 points from his score as he picked a dart off the brick floor. Seriously, why does a bounce out get you 60 points when a t1 that sticks gets you only three? Something is massively screwed up in the Italian space-time continuum.

We called it a night around 11:00 p.m. At least I think we did...

We called it a night around 11:00 p.m. At least I think we did...

Talozzi said, Arrivederci, which I believe means "goodbye" or "until we meet again," or some such thing. If not, he may still be standing at the line at the Piazza della Repubblica. Maybe I was supposed to find him a beer.

I weaved my way back to the Relais Mastro Cinghiale. I was attacked by a horde of Etruscans en route, but still, I had a "whale" of a time.

From the Field,

Dartoid